Between Barbie and Murder: Cambodia 2005

Halfway between here and there, between old and new, between sorrow and joy, and past and present... somewhere between Barbie dolls and senseless murder, there is a place called Cambodia.

Halfway between here and there, between old and new, between sorrow and joy, and past and present... somewhere between Barbie dolls and senseless murder, there is a place called Cambodia.

This article, describing a trip to Cambodia in late 2005, is divided into nine sections:

Part One: Princess of Cambodia

Part Two: Banishing Shadows

Part Three: The Saint of the Deported

Part Four: Trips Taken and Not Taken

Part Five: Spare Days

Part Six: North to the Temples

Part Seven: Ghosts and Wrong Turns

Part Eight: Changed City

Part Nine: The Eight Hundred and Nine Stairs

Part 1: Princess of Cambodia

Cambodia. A half-century ago, the name invoked awe and mystery. It was an exotic kingdom; it meant magnificent wonders hidden in a tropical jungle. Decades later, it came to mean something else: Bombing. War. Genocide. The Khmer Rouge. Killing fields.

"Cambodia" became synonymous with horror. It meant piles of skulls and fields of bones. It was a metaphor for death and ruin.

But over time, memories fade. Wars come and go, as Carl Sandburg observed in Grass:

Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me work -

I am the grass; I cover all.And pile them high at Gettysburg

And pile them high at Ypres and Verdun.

Shovel them under and let me work.

Two years, ten years, and passengers ask the conductor:

What place is this?

Where are we now?I am the grass.

Let me work.

Grass reclaims the battlefields. Rice reclaims the killing fields. Time reclaims our understanding of what happened, why it happened, and how the bodies came to be beneath our feet.

For nearly a decade, my screen name on America Online has been "Cambodia." It was not until 1999 that I began to understand how much -- or how little -- that name meant to different people. In that year, the band Limp Bizkit released a song called "Cambodia." I began to get messages from strangers who assumed, because of my name, that I was a Limp Bizkit fan. Some were genuinely curious about Cambodia; one or two others had no idea that Cambodia was actually a country, and not simply a made-up word that sounded good in the song. If real countries are mistaken for made-up words, perhaps the inverse is true. Maybe there are a handful of Phil Collins fans who believe that "Sussudio" is a small nation somewhere in Africa.

For nearly a decade, my screen name on America Online has been "Cambodia." It was not until 1999 that I began to understand how much -- or how little -- that name meant to different people. In that year, the band Limp Bizkit released a song called "Cambodia." I began to get messages from strangers who assumed, because of my name, that I was a Limp Bizkit fan. Some were genuinely curious about Cambodia; one or two others had no idea that Cambodia was actually a country, and not simply a made-up word that sounded good in the song. If real countries are mistaken for made-up words, perhaps the inverse is true. Maybe there are a handful of Phil Collins fans who believe that "Sussudio" is a small nation somewhere in Africa.

No matter: the flurry of messages made me realize that a growing number of people had never heard of the killing fields, and "Cambodia" meant nothing. The metaphor had begun to fade. The country was finally shedding its horrific past. The definitive evidence? Barbie, Princess of Cambodia.

Mattel, that quintessentially American company, had for years released special editions of the Barbie doll, attired as a princess of one country or another. Barbie, Princess of Ireland. Barbie, Princess of Japan. Barbie, Princess of Thailand.

And then, in 2004, there it was: Barbie, Princess of Cambodia.

This, to me, was proof: in mainstream America, "Cambodia" was no longer automatically associated with genocide and death. Cambodia was, once again, an exotic kingdom, a mysterious place of jungles and temples and lithe dancers in shimmering silk gowns.

How many years does it take to heal? How many years for the grass to do its work? Two years, ten years, twenty-five years. Perhaps someday there will be Barbie, Princess of Kosovo, or Barbie, Princess of Rwanda. Someday.

For now, there are still scars. Ninety years later, in the forest that was once the battlefield of Verdun, there are still spent bullets. In Cambodia, the effects of decades of war remain. A culture of violence lingers beneath the peaceful facade.

This point if driven home to me on June 16, 2005. My wife and I were preparing to take our children to renew their passports. That morning, Cambodia was in the news. From CNN.com:

"A hostage standoff at an international school in Cambodia has ended with the deaths of a Canadian boy and two gunmen, police said.Cambodian police said they captured four other gunmen who had been holding more than 50 elementary school students and teachers hostage for nearly six hours Thursday in the northwestern Cambodian town of Siem Reap.

Authorities said the Canadian boy was killed after being shot in the head by a hostage taker. His age was unclear. All the children were elementary school students, ages 2 through 6.

It is sad beyond words. Senseless violence and shattered hopes. One step forward, one step back.

Sometimes I wonder what Srey, my wife, thinks of Cambodia. Does she think of it as home? She was born and raised in Phnom Penh, and lived in Cambodia until 1992. Yet I can't recall ever hearing her refer to Cambodia as home.

This will be the second time our children have been to Cambodia. Their first trip, however, was five years ago, and I believe that "children years" are something akin to "dog years." For our daughter, the trip was half a lifetime ago; for our son, about two-thirds of a lifetime.

How will it compare to the last trip? In at least one respect, it will be almost identical: It's a Shampoo Extravaganza. As in the year 2000, we're transporting a massive quantity of shampoo. In our luggage, we will carry forty-two pounds of shampoo.

How will it compare to the last trip? In at least one respect, it will be almost identical: It's a Shampoo Extravaganza. As in the year 2000, we're transporting a massive quantity of shampoo. In our luggage, we will carry forty-two pounds of shampoo.

Why do four people need nearly 50 bottles of shampoo for a three-week trip? A similar question gnawed at Gilligan's Island fans week after week: If it was supposed to be a three-hour tour, why did the Howells have all that luggage?

The shampoo isn't for us. Srey insists that people in Cambodia love American shampoo... so, like it or not, we will bestow upon our friends the precious gift of Shiny Hair.

On the day we begin packing, my wife brings out the shampoo and begins wrapping duct tape around the top of the bottles so that they'll be less likely to leak. I take one look at the bottle of heavy liquid with duct tape wound around the top, and my first thought is: Security will not like the looks of that. I imagine these bottles winding up in the same suitcase with an alarm clock and a few bits of stray wire, and me frantically trying to explain to gun-wielding security guards that IT'S JUST SHAMPOO!

I mention this to a friend, who ignores the question of what it will look like. He zeroes in on a more critical issue: "Do you know how lucky you are?" he asks. "Think about it. You're married to a woman whose first solution to a problem is duct tape!"

Aside from the shampoo, we also have a few old laptops; two were donated by the Most Excellent Mike Disbrow, and one was donated by a fine anonymous woman on the marvelous Craigslist Chicago. Hopefully we'll find good homes for them.

To ensure our safety, a monk at the local Buddhist temple blesses us. He ties bright strings around our wrists, and we'll wear them for the duration of the trip... unless, of course, we lose them, which my daughter manages to do a week before we leave. No worries: another trip to the temple, a new string, and we're all set.

To ensure our safety, a monk at the local Buddhist temple blesses us. He ties bright strings around our wrists, and we'll wear them for the duration of the trip... unless, of course, we lose them, which my daughter manages to do a week before we leave. No worries: another trip to the temple, a new string, and we're all set.

This time, we'll be flying from Chicago to Seoul, via Korean Airlines. From Seoul, we'll travel to Bangkok, where we'll spend the night at the airport. Then, the following morning, we'll fly to Phnom Penh. We've stocked up on the essential accessories for air travel: Dramamine, junk food, and lots of books. My wife prefers to listen to music. Anna, nine years old, has chosen Cornelia Funke's Inkspell. Sean, seven, has picked some "Magic Treehouse" books by Mary Pope Osborne, Will Osborne and Ozzy Osbourne. (OK, I made up the bit about Ozzy.) I'm bringing Edith Mirante's Down the Rat Hole, Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything, de Tocqueville's Democracy in America, and Ray Bradbury's One More for the Road and The Martian Chronicles.

I've been reading Martian Chronicles to my children over the past couple weeks, and we'll continue on the trip. Twenty years from now, will they remember? Will they someday see a faded paperback in a bookstore, and remember that their father read it to them in the waiting room at the dentist's office, in the parking lot at the produce store, or in the transit lounge of the airport in Bangkok?

Time, place, and memory: the first one vanishes, and all that remains of the second is the third. It's a convoluted expression of a simple thought: Stop blinking, dammit, you're missing your life.

Part 2: Banishing Shadows

Were it not for Neang Tep, we would have arrived in Cambodia to discover that our luggage was still in Bangkok. Neang, who drove us to the airport, noticed as we were checking in that the ticket agent had tagged our bags for Bangkok instead of Phnom Penh. When you're hauling 500 pounds of old clothing, laptops, DVD players, medicines and cosmetics, you don't wanna lose track of your bags. And you sure as hell don't want to lose your shampoo.

Were it not for Neang Tep, we would have arrived in Cambodia to discover that our luggage was still in Bangkok. Neang, who drove us to the airport, noticed as we were checking in that the ticket agent had tagged our bags for Bangkok instead of Phnom Penh. When you're hauling 500 pounds of old clothing, laptops, DVD players, medicines and cosmetics, you don't wanna lose track of your bags. And you sure as hell don't want to lose your shampoo.

The flight is uneventful. Korea's Incheon Airport is a marvel of cleanliness and efficiency; Bangkok's airport meanwhile, always has more than its share of interesting characters. In the transit lounge, we overhear a man speaking Khmer; he turns out to be an engineer working on demining and the removal of unexploded ordnance.

Arriving at Pochentong, I'm again shocked at how much the airport has changed. It seems to have doubled in size since 2000, and wonder of wonders, they even have jetways.

Outside the airport, the main road into Phnom Penh looks much as it did five years ago. Motorcycles and scooters still dominate, but there are more cars all the time. The highlight of the trip into the center of the city is the game, "Spot the most impossible load on a motorcycle." The winner this time around: a ten-foot tall potted tree.

Srey spends nearly all of the first day handing out the packages and parcels that friends in the United States have asked her to deliver. For overseas Khmer visiting Cambodia, this is a ritual. They will carry as much luggage as is allowed, but the majority will be gifts for families in Cambodia. It's essentially a quid pro quo arrangement. Any Khmer going back puts out the word, and in the final weeks before departure, acquaintances stop by with money or packages to deliver to their relatives.

For many families, having relatives abroad is the difference between abject poverty and financial security. I've often wondered how such impromptu "foreign aid" affects Third World economies. In 1988, a priest named Segundo Montes Mozo conducted surveys to determine the importance of money sent back to El Salvador from relatives in the United States. He came to the conclusion that it was critical to many families: for some, it was essential just to meet basic needs, and for others, it brought about a tangible improvement in the standard of living.

For many families, having relatives abroad is the difference between abject poverty and financial security. I've often wondered how such impromptu "foreign aid" affects Third World economies. In 1988, a priest named Segundo Montes Mozo conducted surveys to determine the importance of money sent back to El Salvador from relatives in the United States. He came to the conclusion that it was critical to many families: for some, it was essential just to meet basic needs, and for others, it brought about a tangible improvement in the standard of living.

Dr. Montes, sadly, was murdered the following year: a Salvadoran army patrol entered the university where he taught, and massacred him along with five other priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter. Welcome to war in the Third World.

Roughly fourteen years ago, on my first visit to Cambodia, I was struck by the sense that the entire country was broken and wounded. The Khmer Rouge were still a viable army, a Sword of Damocles waiting in the jungle. No one felt entirely safe: they were still out there, tens of thousands of them, murderers and fanatics.

By the year 2000, the Khmer Rouge were gone, and the the change in Phnom Penh was stunning. Poverty remained, but at last there were signs of progress. The future didn't look perfect, but at least there would be a future.

Even today, however, beneath the surface, the effects of the Khmer Rouge genocide still linger. How long is the shadow cast by two million deaths?

My wife's father, Sophon Choun, disappeared in 1977. In 2000, we had organized a small ceremony, a bon katin in his memory. My wife had always wanted a more proper ceremony, with more of family friends and the few surviving distant relatives in attendance. This time, Srey, her sister Lung, and their aunt Lavet arrange a much more elaborate bon. A large tent is set up in front of the house, and four monks from a nearby temple will perform the rites. The ceremony will begin on Sunday afternoon.

My wife's father, Sophon Choun, disappeared in 1977. In 2000, we had organized a small ceremony, a bon katin in his memory. My wife had always wanted a more proper ceremony, with more of family friends and the few surviving distant relatives in attendance. This time, Srey, her sister Lung, and their aunt Lavet arrange a much more elaborate bon. A large tent is set up in front of the house, and four monks from a nearby temple will perform the rites. The ceremony will begin on Sunday afternoon.

That morning, we head to Wat Langka, to deliver an envelope from one of the monks in Chicago. Inside the monk's house, the walls are decorated with photos cut from magazines: there is one of Mount Rushmore, one of cactus on a hillside, one of the St. Louis arch, and other tourist spots from around the US.

On the way back, we stop at one of the city's new shopping centers, the oddly-named Pencil SuperCenter. There are four sparkling, gleaming, antiseptic-clean levels of shopping: groceries, books, clothes, toys, the works. It's just the place to find the things you aren't likely to find at the traditional Khmer markets, things like peanut butter, Slim Jims, Fruit Loops.

Once in a while we'll pass some sort of banner offering English lessons or cheap cell phones or some such thing. Other banners, however, are a bit more unsettling. One, attached to the fence outside a college, is written in Khmer. Srey translates: "Sam Rainsy is the person who is destroying politics." Rainsy, an opposition politician, has for years campaigned relentlessly against cronyism and corruption in the government. For his efforts, he was targeted for assassination in 1997, when a grenade attack on a peaceful demonstation killed at least 16 of his supporters, including one of his bodyguards. (Shortly after our trip, Rainsy was sentenced in absentia to 18 months in prison for remarks accusing Primer Minister Hun Sen of involvement in the attack, and for claiming that FUNCINPEC party leader Norodom Ranariddh had accepted bribes to form a coalition government with Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party. Similarly, on December 30, two other well-known activists, Kem Sokha, of the Cambodian Center of Human Rights, and Yeng Virak, of the Community Legal Education Center, were arrested on defamation charges for a banner displayed on International Human Rights Day on December 10. The banner had labeled Hun Sen a "communist" and a "traitor" who had sold Khmer land to Vietnam. Hun Sen, of course, is not a communist... he's just a former communist. Specifically, he is a former Khmer Rouge soldier.)

Once in a while we'll pass some sort of banner offering English lessons or cheap cell phones or some such thing. Other banners, however, are a bit more unsettling. One, attached to the fence outside a college, is written in Khmer. Srey translates: "Sam Rainsy is the person who is destroying politics." Rainsy, an opposition politician, has for years campaigned relentlessly against cronyism and corruption in the government. For his efforts, he was targeted for assassination in 1997, when a grenade attack on a peaceful demonstation killed at least 16 of his supporters, including one of his bodyguards. (Shortly after our trip, Rainsy was sentenced in absentia to 18 months in prison for remarks accusing Primer Minister Hun Sen of involvement in the attack, and for claiming that FUNCINPEC party leader Norodom Ranariddh had accepted bribes to form a coalition government with Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party. Similarly, on December 30, two other well-known activists, Kem Sokha, of the Cambodian Center of Human Rights, and Yeng Virak, of the Community Legal Education Center, were arrested on defamation charges for a banner displayed on International Human Rights Day on December 10. The banner had labeled Hun Sen a "communist" and a "traitor" who had sold Khmer land to Vietnam. Hun Sen, of course, is not a communist... he's just a former communist. Specifically, he is a former Khmer Rouge soldier.)

In the afternoon, the monks arrive for the bon, and they make their way to the second floor, where we will be staying for most of the next three weeks. We sit in front of the monks in the tiny room. They chant and sprinkle us with water, jasmine flowers, and lotus petals. I'm still jet-lagged, and as I sit before the monks, my sleep-addled mind focuses on the can of Sprite sitting in front of the nearest monk. It's hot, very hot, and as the monks chant in ancient Pali, tossing jasmine at us, I keep thinking: "Dude, throw the Sprite!"

The first part of the bon ends fairly early, then resumes at 7am the next morning. The tent in front of the house has been equipped with an amplifier and speakers, and music is playing loudly. Srey walks downstairs and finds a foreigner standing in front of the house, clearly irritated. "May I help you?" she asks. Yes, he replies. The music is too loud, and speaker is right outside his window. He's trying to get to sleep. Srey explains that it will only be this morning, and that it is part of the memorial for her father. He apologizes and retreats.

The first part of the bon ends fairly early, then resumes at 7am the next morning. The tent in front of the house has been equipped with an amplifier and speakers, and music is playing loudly. Srey walks downstairs and finds a foreigner standing in front of the house, clearly irritated. "May I help you?" she asks. Yes, he replies. The music is too loud, and speaker is right outside his window. He's trying to get to sleep. Srey explains that it will only be this morning, and that it is part of the memorial for her father. He apologizes and retreats.

Later, the ceremony continues in Lung's house. At one point Srey's mother (whom we call Yeay) is given the microphone in order to say some sort of prayer. Naturally, like any polite Khmer, she wants to sompeah as she speaks. The problem is that she's clasping the microphone at the bottom, so as she raises her hands, she winds up with the top of the microphone at her forehead. One of Lung's friends reaches out and grabs the old woman's hands and pulls them lower, so that the microphone is at her lips. She lets go, and up goes the microphone again, back to Yeay's forehead. She reaches out again and pull's Yeah's hands back down; this time she won't let go, but Yeay won't give up without a struggle; she continues praying without missing a beat, but fights to keep the mic up at her forehead. The woman finally laughs and gives up, leaving Yeay to murmur incomprehensibly into the bottom of the mic.

Part 3: The Saint of the Deported

Tuesday is a concession to our children: we head to the Phnom Penh Water Park to swim. The water park, on Pochentong Road, is relatively new. It features a swimming pool, water slides, a tube ride, a "beach" with artificial waves, and, according to the signs at the entrance, safely filtered water. There are few people there, and we are the only foreigners.

Tuesday is a concession to our children: we head to the Phnom Penh Water Park to swim. The water park, on Pochentong Road, is relatively new. It features a swimming pool, water slides, a tube ride, a "beach" with artificial waves, and, according to the signs at the entrance, safely filtered water. There are few people there, and we are the only foreigners.

After a couple hours we summon a tuk-tuk for the trip home. The tuk-tuk is essentially a small wagon grafted on to the rear end of a motorcycle. Long popular in Thailand, they were until recent years rare in Cambodia, where the cyclo and the scooter were the preferred mini-taxis.

When we are about halfway home, we get diverted by the police. Cambodia's renowned Water Festival is underway, and there are so many people heading to the river that unapproved traffic is being re-routed. This apparently includes tuk-tuks, so we're forced to change to motorcycle taxis for the remainder of the ride. We ride three-up on the scooters the rest of the way home.

The popularity of the Water Festival is, to me, something of a mystery. The festival brings massive crowds to the waterfront, and I have an aversion to large groups of people. Beyond that, however, the centerpiece of the entire event - the canoe races - just doesn't strike a chord. Sure, those are some long boats. And yeah, that's a whole bunch of guys, rowing pretty fast. But I have no reason to care who wins. Maybe if I knew some of the racers it would be different: put a Khmer Rouge in one boat and Sam Rainsy in another, and I'll know who to cheer for.

In the evening, we take a short ride around Phnom Penh in the back of a friend's pickup truck. We stop to visit one of their relatives, who has a business making artificial feet. The abundance of landmines in Cambodia has resulted in a horrifying number of amputees, changing the very landscape: in the same way that water carves canyons in the land, hidden explosives have carved the population.

In the evening, we take a short ride around Phnom Penh in the back of a friend's pickup truck. We stop to visit one of their relatives, who has a business making artificial feet. The abundance of landmines in Cambodia has resulted in a horrifying number of amputees, changing the very landscape: in the same way that water carves canyons in the land, hidden explosives have carved the population.

One consequence of this tragedy is that Cambodians have acquired significant expertise in the construction of artificial limbs. Our host notes proudly that his feet are now being exported to other countries, since the quality is excellent; they're cheap and durable. He holds up a sample as I take his picture: the man with three feet.

Driving around the city, one is struck by the sudden differences from one street to the next. Turn off the main roads, and you may find yourself bouncing in darkness down an unlit, rutted dirt alleyway, lined by crude shacks on both sides. Turn back to the main road, and you are suddenly awash in the bright neon and glowing flourescent lights of a new department store.

The following morning, we head north out of the city toward Oudong. At one time the capital of Cambodia, Oudong is popular mainly for its mountaintop temple. The drive takes about an hour. If you want to reach the top, be prepared to climb lots of steps. Have a good supply of small-denomination Cambodian currency ready; as with many such destinations, the approach to the temple will be lined with beggars. You'll also probably have an entourage of helpful children, whether you want them or not: they will follow you all the way up, fanning you and offering tidbits of information about the temple and the customs.

At the beginning of the ascent, we purchase incense and lotus blossoms to lay at the alter of the temple. Halfway up, however, a monkey steals the lotus stems right out of Sean's hand.

The view from the temple is impressive. The landscape below is dotted with forest, rice fields, and the occasional stupa.

The view from the temple is impressive. The landscape below is dotted with forest, rice fields, and the occasional stupa.

Back in Phnom Penh in the afternoon, we visit a man named Bill Herod. For years, Herod has worked tirelessly to... to do what, exactly? I'm looking for a concise way to put it, and the most accurate rendition is too simple to be eloquent: He does good things.

For at least a decade, Herod has done whatever needed to be done, which wasn't being done by anyone else. He is generally regarded as the father of the Internet in Cambodia, having brought the first Internet connection to Phnom Penh in 1997.

Herod's current project is the Returnee Integration Support Program (http://rispcambodia.org/). In 2002, the United States began deporting resident alien Cambodians who had been convicted of felonies. As Herod points out, this is not especially unusual: virtually any country in the world will deport criminals to their home country. What is unique in the case of Cambodian deportees is that many of them have no tie whatsoever to Cambodia. They may have spent years in refugee camps in Thailand, then come to America as children. As refugees, they were eligible for citizenship, but many never bothered to apply. Instead, they remained resident aliens. Some cannot speak Khmer, and have no family and no friends in Cambodia.

Shortly after the deportations began, Herod discussed the difficulties and dangers faced the returnees -- and in some cases, the dangers posed to others by the returnees -- with representatives from several NGOs. Everyone agreed that something needed to be done... but no one particularly wanted to be the one to have to do it. In the end, it was Herod who took the initiative.

Herod is hardly a bleeding heart; he makes no excuses and does not preach. His easygoing manner, however, is deceptive. Faced with a problem, his natural impulse is to do something to alleviate it.

Herod is hardly a bleeding heart; he makes no excuses and does not preach. His easygoing manner, however, is deceptive. Faced with a problem, his natural impulse is to do something to alleviate it.

As of November 2005, there are about 1400 Cambodians facing deportation. Herod's hope is that the current policy will be amended to include a case-by-case review. A shoplifter is dealt with in the same manner as a murderer. Without a review process, the policy at times becomes Kafkaesque. The Christian Science Monitor reported that one man was deported for trying to visit his children in violation of a restraining order that had been obtained by his wife. (For details see http://www.csmonitor.com/2003/0121/p08s01-wosc.html) CNN cited the case of another man - whose parents had both been murdered by the Khmer Rouge - who had a wife and two young children in Houston, and a job as a construction supervisor. He was arrested for indecent exposure for urinating on the job site. After violating his parole, he served four years in prison, and was then deported. (Details at http://edition.cnn.com/2002/WORLD/asiapcf/southeast/11/19/cambodia.returnees/ and http://www.hyphenmagazine.com/features/issues/summer03/strangers.php)

In such cases, the word deported does not convey the magnitude of the punishment. They lose their homes. They lose their families. They lose their life savings. They lose everything, and they are exiled to a country that they do not know... and this can occur after they have already served the sentences for their crimes.

Herod's facility provides lodging for new returnees, providing them with a haven until they can establish themselves in what is, for many of them, an alien land. The building is also a guest house and an internet cafe; this, hopefully, will help to offset some of the group's expenses.

On the way out, I notice two signs which say something about Herod's nature. The first states that drugs are not allowed on the grounds. "If you want a second warning," it concludes, "read this again." The second sign is quite different: it is a flyer seeking information on a young British man, last seen at a nearby bar. The man had disappeared more than a year ago. There was no particular reason why his disappearance should have been Herod's concern. And yet Herod had met with the man's parents, and the flyer was still prominently displayed. In a way, it seems symbolic of Herod's approach to everything: Do what you can. Hold out hope.

Part 4: Trips Taken and Not Taken

On Thursday morning, we leave at 4AM for a trip to Sihanoukville (or, if you prefer, Kompong Som. The name has changed a few times over the years. Sihanoukville seems to be the current favorite.) Traffic is light, and we make good time, even without relying on the standard Cambodian practice of laying on the horn to force all the smaller vehicles to the side of the road.

On Thursday morning, we leave at 4AM for a trip to Sihanoukville (or, if you prefer, Kompong Som. The name has changed a few times over the years. Sihanoukville seems to be the current favorite.) Traffic is light, and we make good time, even without relying on the standard Cambodian practice of laying on the horn to force all the smaller vehicles to the side of the road.

In the darkness before sunrise, it's difficult to see many of the smaller vehicles. A number of wagons and lorries that have addressed this problem by tacking old compact disks to the back of the vehicle to serve as makeshift reflectors.

The monotony of the drive is broken up by a stop to buy bread at a busy market town, about a half hour out of Sihanoukville. Vendors are selling dried fish and squid, live crabs, bread, coconuts, and plenty of other foods that I can't even identify. The driver goes in search of something or other, and as we wait in the van, a scraggly-looking, bearded man, stark naked, walks past.

I'm certain that this is not at all a common occurance, but it reminds me of a similar incident on my first visit to Cambodia. Waiting for a ferry at Neak Loung, a man in a loin cloth had approached a Vietnamese woman selling prawns. Speaking loudly in I-don't-know-what language, he grabbed a shrimp and marched off. Bewildered, the woman just shrugged and laughed.

Just about the time the driver returned, the naked guy, who for some reason reminded me of Cat Stevens, walked past going the other way. Nobody paid much attention to him, but from observation, I can say being naked seems to be an effective way to get everybody out of your way in a crowded market.

By the time we reach Sihanoukville, the sun is up, and the day is warm. The water, too, is warm. Those of us who don't mind getting drenched take a short ride on a "banana boat." The banana boat is simply a large inflatable tube, with two smaller tubes on either side for stability. It's big enough to seat five or six people, and is pulled behind a motorboat. At the end of the ride, the driver turns sharply, throwing everyone off into the water.

In the early afternoon, the sky darkens and showers approach quickly. A light rain arrives and departs.

In the early afternoon, the sky darkens and showers approach quickly. A light rain arrives and departs.

On the return trip, we head toward Kampot. The roads are in worse shape, but the landscape is more interesting: rice fields in the foreground, mountains behind, and from time to time, a glimpse of the Gulf of Thailand. Fog-shrouded mountains rise up to our left. Once a resort area for the wealthy, the mountains today are virtually uninhabited. Poor roads and perpetual fog have thus far stymied attempts to develop the area. Only a handful of tourists visit the area, drawn by the "ghost town" aura of abandoned resorts like the once-luxurious Bokor Palace Hotel. (On this site, Antonio Graceffo describes hiking into Bokor. Elsewhere on the web, Andy Brouwer's excellent website has photos at http://www.btinternet.com/~andy.brouwer/bokor.htm.)

The harsh nature of the mountains was exploited by the Khmer Rouge during the Eighties and Nineties. In 1994, three tourists - David Wilson, Mark Slater, and Jean-Michel Braquet - were among those captured when Khmer Rouge guerrillas attacked a train. They were later executed. The officer who ordered the killings, Chhouk Rin, was eventually apprehended, and is one of only a handful convicted for the mind-numbing atrocites committed by the Khmer Rouge over the course of some thirty years.

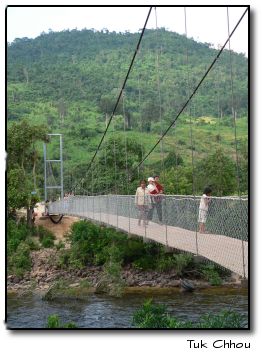

In the late afternoon we stop briefly at Tuk Chhou, a site popular for a small, fast-moving river fed by mountain springs. A suspension bridge over the river offers a view of visitors cooling down in the shallow water. On the other side of the bridge, a small pasture seems populated mainly by dragonflies. Srey amazes our children with her ability to snare the insects by the tail.

By the time we reach Phnom Penh, it's nighttime, and we're exhausted. Our driver will return in the morning, and we'll head to Siem Reap.

By the time we reach Phnom Penh, it's nighttime, and we're exhausted. Our driver will return in the morning, and we'll head to Siem Reap.

Or so we thought.

We get up at 7 to prepare for the trip to Siem Reap. Sean complains of a stomach ache. He had eaten very little the day before, so I chalk it up to hunger. The van arrives, and we begin loading our bags. Srey is heading downstairs with Sean when suddenly, at the foot of the stairs, he vomits.

One of the neighbors, a doctor, is passing by at the very moment Sean gets sick. Most likely something he ate, says the doctor. We decide to postpone the trip. By mid-morning, Sean seems fine, eating everything in sight and drinking huge amounts of Coke. We spend most of the day resting. The delay turns out to be a blessing; nearly everyone was exhausted from long trip back through Kampot, and no one was looking forward to another day in the van. We decide to leave for Siem Reap the following morning, and spend the day relaxing around the house; Anna goes with two of her cousins and a neighbor to an upscale mall, returning with a stuffed tiger and a Spiderman mask for her brother.

The following morning, Sean seems fine. However, as I look at Anna, who is still sleeping, I start to get a little uneasy: her face looks tight, as though she's in pain. Sure enough, when I wake her up, she tells me that her stomach hurts.

The moment the van arrives, we find ourselves in a replay of the previous day, with Anna in the role of "vomiting child." Once again, there will be no trip.

Part 5: Spare Days

To keep the kids from getting horribly bored when we're not going somewhere, we've brought several DVDs. Among them is The Complete Bean, featuring Rowan Atkinson as Mr. Bean.

To keep the kids from getting horribly bored when we're not going somewhere, we've brought several DVDs. Among them is The Complete Bean, featuring Rowan Atkinson as Mr. Bean.

Apparently, Mr. Bean is quite popular in Cambodia. This is easy to understand: Atkinson's rubber face and bizarre physical comedy transcends language, and there's very little dialogue in most episodes anyway.

For some reason, however, Cambodians seem to think that Rowan Atkinson is dead.

I've encountered this in Chicago, when one of our Khmer friends told my wife this; and sure enough, while my children were watching an episode with their cousins, someone asked if we knew that Atkinson was dead.

Perhaps he can show up at Angkor with Angelina Jolie, and put an end to the greatly exaggerated rumors of his untimely demise.

In the evening, while the two small humans recuperate in the house, Srey and I attend a dance program at Sovanna Phum. The Sovanna Phum Association (#111, St. 360, Phnom Penh, sovannaphum@camintel.com) is dedicated to supporting Khmer art. The program is a combination of traditional dance and shadow theatre. Cambodian shadow theatre is performed with elaborate screens cut from leather; calling them puppets is somewhat misleading. The screens are also available for sale at Sovanna Phum, and would make a fine souvenir.

The following morning, we venture out in search of a refrigerator. What's a trip to another continent without appliance shopping? We'll use it for a couple weeks, then it will be Lung's. We're looking for something small, the type of under-counter refrigerator that you might find in a college dorm room. Most Cambodians do not have refrigerators; this is partly why shopping is such a different experience. Instead of buying a week's worth of meat and fish, they buy what they plan to cook that day, because it's difficult to store.

We settle on a tiny Toshiba, but the other choices are marvelous in a goofy, exotic, tacky way. Maybe you'd like a refrigerator in glowing sea green, or bright turquoise. Or, better yet, how about one with a serene photographic scene of a white sand beach, shaded by palm trees?

We settle on a tiny Toshiba, but the other choices are marvelous in a goofy, exotic, tacky way. Maybe you'd like a refrigerator in glowing sea green, or bright turquoise. Or, better yet, how about one with a serene photographic scene of a white sand beach, shaded by palm trees?

Venturing around Phnom Penh, you'll eventually notice something peculiar: the astonishing market dominance of the Toyota Camry.

The number of Camrys is positively amazing. Something like two out of every three sedans are Camrys. The Mother of All Toyota Salesmen must have taken up residence in Cambodia. There are a fair number of trucks and SUVs of various make and model. Among sedans, however, there is no question: this is the Kingdom of Camrybodia.

In the evening, we return with our children to Sovanna Phum for another performance; this one, called "The Story of the Dog," is a mixture of shadow puppets and conventional puppets. In the end, it's a split verdict: our seven-year-old pronounces it "cool," while the ten-year-old declares it "boring."

Sean is still feverish, so it's off to the doctor. (Naga Clinic, 11 Street 254, Phnom Penh, www.nagaclinic.com). The verdict: a virus, coupled with a slight throat infection. The doctor prescribes an antibiotic, along with Paracetemol. Paracetemol is the French name for Acetominephin. (As Steve Martin once said: "It's like those French have a different word for everything!").

In the early evening, to placate our children's longing for the virtual world, we take them to an internet cafe for an hour. Cafe is not quite the right term, since they don't actually serve anything other than canned drinks. The children are relieved to learn that the Internet is still out there, even if it is excruitiatingly slow.

Later that evening, Anna and Sean are delighted to find that a gecko has taken up residence on the living room ceiling. They immediately name the gecko Jub-Jub, after Aunt Selma's pet Iguana in The Simpsons. This results in a surreal exchange between the children and their Aunt Lung. The Khmer name for the gecko is jing-jot. Hearing the children shout "Jub-jub!" Lung attempts to correct them:

Later that evening, Anna and Sean are delighted to find that a gecko has taken up residence on the living room ceiling. They immediately name the gecko Jub-Jub, after Aunt Selma's pet Iguana in The Simpsons. This results in a surreal exchange between the children and their Aunt Lung. The Khmer name for the gecko is jing-jot. Hearing the children shout "Jub-jub!" Lung attempts to correct them:

"Jing-jot!" she says.

"Jub-jub!" comes the reply.

Lung shakes her head. "Jing-jot."

"Jub-jub!"

Lung picks up a broom and lifts it up close to the gecko, sending the gecko darting across the ceiling with amazing speed. Eventually she corners it and catches it in her hand, an act that impresses the children in much the same way that they were impressed by their mother's ability to snare the dragonfly at Tuk Chu.

The next morning, we have lunch at Thom Tan's home. It has changed greatly since 1991; Thom's brother Narath, who lives in Chicago, paid to have a loft added inside the space. Many old buildings in Cambodia were built with very high ceilings, high enough to accomodate a sleeping loft with standing room beneath. Interior space is precious, and it is conserved in every way possible; staircases, for example, tend to be incredibly steep, thereby minimizing the amount of lost living area.

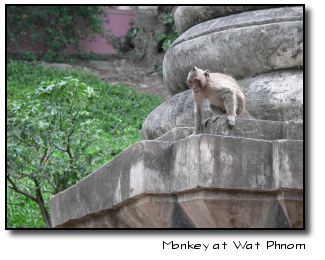

In the afternoon, we visit Wat Phnom. Like most spots frequented by tourists, the stairs to the temple are lined with beggars - the blind, the old, the infirm, and Cambodia's ubiquitous amputees. For anyone who has not visited Cambodia previously, the number of amputees is shocking. Those familiar with Cambodia's history will be less surprised. Scholar Craig Etcheson has argued that Cambodia's tortuous history can be seen in large measure as a single, thirty-year war, with the Khmer Rouge at the center of the drama. The amputees are the most visible reminder of the extensive use of landmines during the last three decades of the Twentieth Century.

In the afternoon, we visit Wat Phnom. Like most spots frequented by tourists, the stairs to the temple are lined with beggars - the blind, the old, the infirm, and Cambodia's ubiquitous amputees. For anyone who has not visited Cambodia previously, the number of amputees is shocking. Those familiar with Cambodia's history will be less surprised. Scholar Craig Etcheson has argued that Cambodia's tortuous history can be seen in large measure as a single, thirty-year war, with the Khmer Rouge at the center of the drama. The amputees are the most visible reminder of the extensive use of landmines during the last three decades of the Twentieth Century.

Today, Wat Phnom looks much as it did years ago. An elephant, looking old and tired, still carries riders around the circle at the base of the temple. The monkey population seems to have grown dramatically. Vendors carry baskets of snacks, incense, lotus blossoms, postcards, and even baskets of books about Cambodian history: David Chandler's Voices from S-21, Ben Kiernan's How Pol Pot Came to Power, Vann Nath's A Cambodian Prison Portrait, and a host of others. Foreigners pay one dollar to visit Wat Phnom; for Khmer (including, apparently, half-Khmer children), it's free.

One change in Phnom Penh is the proliferation of cell phones. A similar phenomenon can be seen in many countries where poverty prevented the development of an extensive infrastructure of land lines. It's cheaper and simpler to implement cell service, so there are more cell phones than land phones.

There are other ways in which Cambodia is increasingly connected with the outside world, as well. One example can be seen in the Thai Huot Market (99-105 Monivong Blvd.), where artificial Christmas trees are on sale for the upcoming holiday. Homesick foreigners can also find the comforts of home at nearby Bayon Market (133 Monivong Blvd.): Fruit Loops, Chef Boyardee spaghetti, Miracle Whip, coffee ice cream... mmm, what could be better?

That evening, since it's Anna's birthday, we prepare a small party in front of the house. Anna is upstairs, putting on a dress that Thom has made. Just as she is about to come downstairs to show off her new dress, the entire block blacks out. The children out front begin to cheer and clap. We go searching for candles and flashlights, continuing preparations in the dark. After 15 or 20 minutes, by the time we've tracked down candles and lit them, the streetlights begin to glow again, though the houses are still without power. A neighbor offers the space in front of her house, directly below the streetlight, as a place to host the birthday cake. After the cake, it's time for the highlight of the party: clay pot pinatas. The makeshift pinatas were Srey's idea, a workaround that she had employed on our last visit to Cambodia. The pots are filled with candy and suspended from a cord between a tree and the streetlight. They're perfect for the purpose: just sturdy enough to sometimes take a hit without breaking. Nearly every child on the street shows up for a chance to smash the "pinatas," and it still takes a full ten minutes before both pots have given up their candy.

That evening, since it's Anna's birthday, we prepare a small party in front of the house. Anna is upstairs, putting on a dress that Thom has made. Just as she is about to come downstairs to show off her new dress, the entire block blacks out. The children out front begin to cheer and clap. We go searching for candles and flashlights, continuing preparations in the dark. After 15 or 20 minutes, by the time we've tracked down candles and lit them, the streetlights begin to glow again, though the houses are still without power. A neighbor offers the space in front of her house, directly below the streetlight, as a place to host the birthday cake. After the cake, it's time for the highlight of the party: clay pot pinatas. The makeshift pinatas were Srey's idea, a workaround that she had employed on our last visit to Cambodia. The pots are filled with candy and suspended from a cord between a tree and the streetlight. They're perfect for the purpose: just sturdy enough to sometimes take a hit without breaking. Nearly every child on the street shows up for a chance to smash the "pinatas," and it still takes a full ten minutes before both pots have given up their candy.

The children positively love it, and it makes me wonder if a new tradition will take hold: will we come back in five years, ten years, and find that children's parties in Phnom Penh always include a clay pot pinata?

In the morning, Srey finds a spider behind the door of the bedroom. It's not particularly big by Cambodian standards, but if you found it in your bedroom in Chicago, you'd be saying, "Holy crap, that is a huge spider!" I try to smack it with a broom, but it darts away. Srey tries, and manages to get it trapped in the broom's soft bristles, allowing her to release it outside. An hour later, it's relaxing on the outside wall, none the worse for wear. We relax at the house all day and prepare for another attempt at Siem Reap the next morning.

In the morning, Srey finds a spider behind the door of the bedroom. It's not particularly big by Cambodian standards, but if you found it in your bedroom in Chicago, you'd be saying, "Holy crap, that is a huge spider!" I try to smack it with a broom, but it darts away. Srey tries, and manages to get it trapped in the broom's soft bristles, allowing her to release it outside. An hour later, it's relaxing on the outside wall, none the worse for wear. We relax at the house all day and prepare for another attempt at Siem Reap the next morning.

Part 6: North to the Temples

On Thursday morning we head north out of Phnom Penh, traveling through Kompong Cham and Kompong Thom. Thom Tan tells me that in the late 1980s, when he was working as a classical dancer, he had taken the same road. In those days, it was a rutted, broken path through an area that was virtually uninhabited because of the presence of the Khmer Rouge guerrillas in the surrounding countryside.

Now, the road is newly paved and marvelously smooth. We sail smoothly along in an air-conditioned van, passing gleaming new tourist buses. A Lexus SUV with California license plates passes us and barrels down the road ahead.

Now, the road is newly paved and marvelously smooth. We sail smoothly along in an air-conditioned van, passing gleaming new tourist buses. A Lexus SUV with California license plates passes us and barrels down the road ahead.

More traditional traffic is also apparent: scooters, bicycles, lorries pulled by small ponies, and the occasional cow.

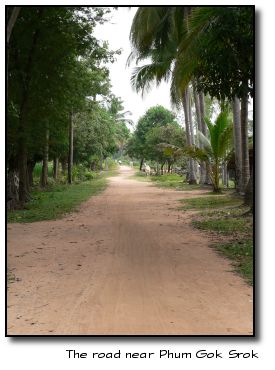

We have one stop to make near Siem Reap. A friend in Chicago has a sister living near a small village called Phum Gok Srok, just outside of Siem Reap city. We're to deliver three hundred dollars to her.

We turn off the main road, passing by the ancient ruins of the Bakong temple. The road becomes a narrow dirt path, scarcely wide enough for the van.

In 1991, on of the women who had traveled with me to Cambodia had a brother living in the rural Siem Reap. When she arrived in Phnom Penh, she had hoped that her brother or one of his children would come to visit her. In the end, however, no one could contact him: the area was so heavily mined that no one was willing to travel to his home to tell him that his aunt had arrived.

We stop for directions to the house, and I see a heartbreaking reminder that the legacy of those years remains: a small boy, surely no more than seven or eight years old, hurries across the road. He is missing one leg, but moves quickly on his crutches. The ease with which he moves suggests that he has been on crutches for a very long time.

He is my son's age. I look back at my son, who is holding a stuffed dinosaur, and I try very hard to suppress the image in my mind's eye, of my own child in that boy's place.

According to a Xinhua news item from November 25, "The Cambodian Mine/UXO Information System's latest report shows that mines or UXO injured or killed 36 in October, bringing the total number of dead or injured so far in 2005 to 775."

Seven hundred and seventy-five casualties, added to the toll of a war that ended years ago.

We find our friend's sister and continue on. At the outskirts of the village, we pass a new well, bearing a sign indicating that it was donated by "Wisconsin's People." I wonder how it came to be there, an inexplicable bit of kindness from strangers in a frozen northern farmland, most of whom will surely never find themselves in need of a drink in a faraway place called Phum Gok Srok.

By mid-afternoon, we're reached Siem Reap city, and we rent rooms at the Bunnath Guest House (bunnath_gh@hotmail.com). It's $15 a night for a room with two beds, air conditioning, cable TV, and hot water.

At Srey's suggestion, our first stop is the Cambodian Cultural Village (http://www.cambodianculturalvillage.com). The Cultural Village can best be described as a tourist trap. In theory, it presents a representative sampling of different aspects of Cambodian culture. There are dance performances, Chinese temples, Cham temples, a man-made lake, a fake mountain, a small museum with historical artifacts, a theatre. There are also plenty of employees, trying to sell you tacky plates with your digital picture printed in the middle. Oh, joy.

At Srey's suggestion, our first stop is the Cambodian Cultural Village (http://www.cambodianculturalvillage.com). The Cultural Village can best be described as a tourist trap. In theory, it presents a representative sampling of different aspects of Cambodian culture. There are dance performances, Chinese temples, Cham temples, a man-made lake, a fake mountain, a small museum with historical artifacts, a theatre. There are also plenty of employees, trying to sell you tacky plates with your digital picture printed in the middle. Oh, joy.

The Cambodian Cultural village bears roughly the same resemblance to Cambodia as Disneyland's Main Street U.S.A. bears to a typical American city.

For students of history and politics, however, there is indeed something here worth seeing.

It's to be found in the wax museum. The museum features nicely-designed dioramas featuring figures from Cambodian history. There is Jayavarman VII, Penn Nouth, Chinese explorer Chou Ta-Kuon, Sihanouk's mother and father, Ang Doung, singer Sin Sisamouth, and others. It's the next-to-last figure which is most interesting: An UNTAC peacekeeper.

UNTAC - the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia - came to Cambodia in 1992 in an attempt to end the long-running war between the Heng Samrin/Hun Sen regime, and a coalition of three guerrilla groups, including the Khmer Rouge. According to the terms of the peace accords, UNTAC was supposed to administer the country while the four warring factions disarmed, whereupon a new government would be chosen in democratic elections. It was the largest and most costly peacekeeping enterprise ever undertaken by the United Nations. Some 22,000 soldiers and other personnel came to Cambodia with the goal of ending the conflict. It quickly became apparent that things were not going to go as smoothly as the UN had hoped. The Khmer Rouge dropped out of the process and launched attacks against innocent civilians and UN peacekeepers alike. The Hun Sen faction, meanwhile, orchestrated a campaign of murder and intimidation against supporters of the other three factions. In the end, however, the elections took place on schedule, with an impressive turnout. The cost to the UN: $1.6 billion, and 83 dead, including 21 from hostile action.

So how is the UNTAC soldier portrayed in the Cambodian Cultural Village? Is he shown guarding ballot boxes? No... he is shown exiting a bar with a miniskirt-clad hooker on his arm. This, in effect, represents the official government position on the role of the United Nations.

So how is the UNTAC soldier portrayed in the Cambodian Cultural Village? Is he shown guarding ballot boxes? No... he is shown exiting a bar with a miniskirt-clad hooker on his arm. This, in effect, represents the official government position on the role of the United Nations.

Depending on your point of view, this might be funny, sad, fair, unfair, or some mixture of all of these. UN soldiers were notorious for whoring and drinking, and the UN's Chief of Mission - Yasushi Akashi - did not help matters when he replied to criticisms of the peacekeepers' behavior with the indifferent remark that "boys will be boys."

Nonetheless, it is hard to imagine just how insulting this display would be to the families of the soldiers who lost their lives in trying to bring democracy to Cambodia.

Hun Sen, of course, has little use for democracy, particularly since he lost the 1993 election. By threatening to renew the war, he bullied the UN into accepting him as "co-Prime Minister." He subsequently seized complete control in a coup roughly four years later.

While the Cultural Village is a private venture, there is no question that it would not be there if the ruling Cambodian Peoples Party objected. It's also entirely consistent with Hun Sen's speeches, in which he claims that the only thing the UN brought to Cambodia was AIDS.

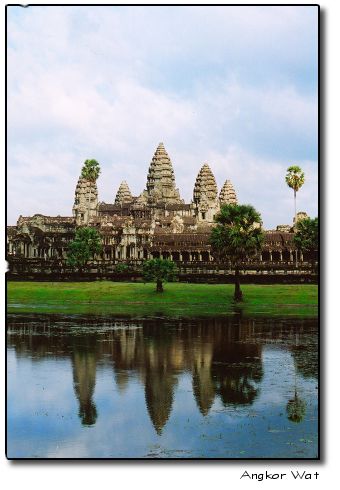

Leaving the Cambodian Cultural Village, we head to Angkor. The price for farangs like me is $20, or $40 for a three-day pass. Arriving late in the day, however, has its advantages: if you purchase a pass after 5pm, you'll be allowed in for the remainder of the evening, and the next day. Thanks to their Khmer mother, our children again get the benefit of the doubt, and get free admission. Or maybe they just get in free because they're still not full-size.

Leaving the Cambodian Cultural Village, we head to Angkor. The price for farangs like me is $20, or $40 for a three-day pass. Arriving late in the day, however, has its advantages: if you purchase a pass after 5pm, you'll be allowed in for the remainder of the evening, and the next day. Thanks to their Khmer mother, our children again get the benefit of the doubt, and get free admission. Or maybe they just get in free because they're still not full-size.

For the moment, we pass Angkor Wat to climb Bakheng. A temple at the top of the hill overlooks Angkor Wat, and it's a popular spot in the evening and morning, when the sun bathes Angkor Wat in a warm Kodachrome glow. Playing the role of pint-sized adventurers to the max, Sean and Anna make it all the way up the crumbling path to the top of the hill, then manage to climb the narrow, steep sandstone steps to the very top of the temple. They bask in their glory as the smallest conquerers of the mountain, until some fifteen minutes later when an even smaller boy shows up.

The day is overcast, so we're robbed of that postcard-pretty shot of Angkor Wat in the setting sun. No matter: the view is still impressive.

Incidentally, if you want to make it to the top of the temple in the evening crowds, there's a trick: don't bother with the front stairway. Walk around to the side, or the back. The stairs there are equally steep, but they'll be far less crowded.

By the time we make our way to the bottom of the hill, it's getting dark, and we retreat to the hotel.

By the time we make our way to the bottom of the hill, it's getting dark, and we retreat to the hotel.

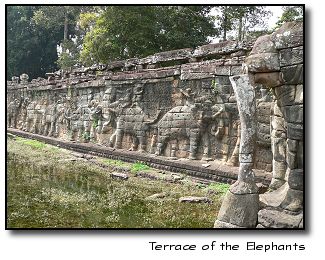

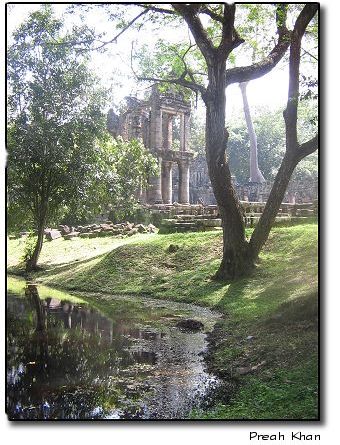

Our first stop the next morning is Angkor Thom. There are several temples within the Angkor Thom complex. Particularly impressive are the Terrace of the Elephants and the Terrace of the Leper-King, long stone walls adorned with elephants and garudas. Next, we stop briefly at Bayon, where a crew of workmen are sawing timber into planks using a two-man tandem saw. Then it's on to Preah Khan.

Preah Khan is surely one of the most underappreciated temples in the Angkor complex. Angkor Wat gets far more attention than the other temples. Angkor Wat is not just the largest temple at Angkor; it is, by most accounts, the largest religious building the entire world. Whether or not this is true probably depends on what one considers part of the building. If one includes the outermost wall and the stone causeway across the lake, it is almost certainly the largest.

To me, however, both Bayon, with its hundreds of stone faces, and Ta Prohm, with massive trees overgrowing the stones, are more interesting. Preah Khan, too, is marvelous. A long path through the jungle leads to a causeway lined with stone guardians and an enormous gate. Inside, the temple stretches on and on.

To me, however, both Bayon, with its hundreds of stone faces, and Ta Prohm, with massive trees overgrowing the stones, are more interesting. Preah Khan, too, is marvelous. A long path through the jungle leads to a causeway lined with stone guardians and an enormous gate. Inside, the temple stretches on and on.

The path to Preah Khan cuts through a long stretch of forest, and as we are walking out, Srey points to the tangled undergrowth and laughs. "When I see this, it reminds me of 1979," she says. She had to venture into the forest to find firewood for cooking. The brush was so thick, however, that it was difficult to drag pieces back out. Young children proved much better at weaving through the dense growth, and she had to settle for the nearby small branches that the children didn't want.

Outside Ta Prohm, we sit down to rest in front of the temple, where a short stone causeway leads across a tree-lined pond. Srey points down at the black water. This, too, reminds her of 1979. Settling briefly in Prey Veng province, she found that the Khmer Rouge had thrown bodies into the wells, and the stench of death and decay hung over the fouled black water.

In the afternoon, we eat lunch at an open-air cafe near the entrance to Angkor Wat. A cat comes to sleep under the table while we eat, and two small girls try to persuade us to buy bracelets. They speak English in unison, twin parrots working from a script of one-liners. "Where are you from?" they ask. "We are from Canada," I lie. "Where are you from?"

"We are from the moon," they say. They hold out the bracelets. "You buy for your girlfriend?"

"We are from the moon," they say. They hold out the bracelets. "You buy for your girlfriend?"

"Oh, no. I don't buy anything for my girlfriend."

"Sir, you buy for your girlfriend!"

"No, thank you."

"If you don't buy she don't love you!"

"No, no thank you."

"Sir, you make me feel upset!" they proclaim.

This last remark, delivered with a show of well-rehearsed synchronized sadness, amuses Srey so much that she decides to buy them off. "OK," says Srey, laughing. "Now I don't buy anything but I pay you."

Not to be outdone in generosity, one of the girls gives Srey a drawing of a flower to remember her. She writes her name, Parry, on the top of the drawing.

After lunch we walk to Angkor Wat. As we enter the inner compound, Srey points out one Apsara, smiling wider than the rest. This, Srey says, is the only apsara whose teeth can be seen. Popular folklore has it that she was being tickled by a monkey behind her.

We make our way to the top of the temple. It offers an impressive view of the surrounding jungle. Once you are at the top, however, it's a little difficult to find your way back down. This is because the stairs are so steep that you can't see them until you step out to the very edge of the tower and look straight down. Standing back from the edge, even a few feet, you can't see the steps at all.

We make our way to the top of the temple. It offers an impressive view of the surrounding jungle. Once you are at the top, however, it's a little difficult to find your way back down. This is because the stairs are so steep that you can't see them until you step out to the very edge of the tower and look straight down. Standing back from the edge, even a few feet, you can't see the steps at all.

Leaving Angkor, we head to the outskirts of Siem Reap, past the new airport, where a massive Air Vietnam jetliner is touching down. The airport, it turns out, is a mixed blessing. It has hurt the tourist business in Phnom Penh, since many visitors now fly directly to Siem Reap from Thailand, Singapore, and other cities abroad.

We stop briefly at the West Baray reservoir. Built sometime around the 11th century, it is astonishing to realize that this massive lake was excavated by hand. There is a small temple in the island in the middle of the lake; it was too late to go to the island, however, so we head back to the hotel to rinse off the dust and sweat.

In the morning, we toy with the idea of visiting Beng Mea Lea, a temple deep in the jungle about 60 kilometers from the other temples. Unfortunately, the weather looks a little threatening, and it turns out that I'm the only one who really likes the idea of bouncing across rough dirt roads for a couple hours just to see one more temple.

We ditch the Beng Mea Lea idea and instead head across town to the Siem Reap Crocodile Farm. In the cool morning, the crocodiles are nearly all motionless. At first, they don't even look real; they look like concrete models, covered with mud and left to rot in an abandoned corner of an old theme park. Once in a while, though, one will suddenly spring into motion, and you're suddenly reminded that you are looking at very, very dangerous animals.

We ditch the Beng Mea Lea idea and instead head across town to the Siem Reap Crocodile Farm. In the cool morning, the crocodiles are nearly all motionless. At first, they don't even look real; they look like concrete models, covered with mud and left to rot in an abandoned corner of an old theme park. Once in a while, though, one will suddenly spring into motion, and you're suddenly reminded that you are looking at very, very dangerous animals.

On the way back to Phnom Penh we stop at Phnom Santuk, a mountain temple in Kompong Cham province. The legion of pint-sized guides accompanying us as we ascend the stairs inform us (several times) that there are 809 steps to the top. This is perhaps not an ideal undertaking for a hot, muggy day. The trip up the stairs is much like that at Oudong, but what greets you at the top is very different: an eclectic collection of old buildings, buddhas, and stupas.

On the way back down, one of the guides - a teenage boy - is holding my daughter's hand. The boy and another girl are talking, but I'm paying no attention.

I will not know what was said until weeks later, when my wife relates the story in the darkness before dawn, thousands of miles away.

Part 7: Ghosts and Wrong Turns

We spend most of Sunday visiting with friends in Takhmau. The children amuse themselves by pursuing geese, bunnies, and a rooster. Monday is similarly uneventful; we relax in Phnom Penh, venturing out for a trip to Monument Books (No. 111, Norodom Blvd.) to pick up a few things to read. Not only does Monument Books have an outstanding selection of books about Cambodian culture and history (in several languages), they also have many general-interest titles as well. Just the place when you have one kid who is dying to read stories about ancient Egypt, and another who is convinced that he needs yet another book about dinosaurs.

We spend most of Sunday visiting with friends in Takhmau. The children amuse themselves by pursuing geese, bunnies, and a rooster. Monday is similarly uneventful; we relax in Phnom Penh, venturing out for a trip to Monument Books (No. 111, Norodom Blvd.) to pick up a few things to read. Not only does Monument Books have an outstanding selection of books about Cambodian culture and history (in several languages), they also have many general-interest titles as well. Just the place when you have one kid who is dying to read stories about ancient Egypt, and another who is convinced that he needs yet another book about dinosaurs.

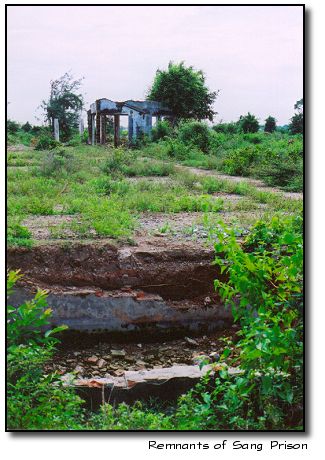

On Tuesday morning, our plan is to visit Tonle Bati. Tonle Bati is the site of an 11th century temple, and it's also a popular lakeside resort. Across the lake, however, is another historical site with a far darker past. Known locally as Sang Prison, it was an execution facility during the Khmer Rouge years.

I want to see Sang.

It's difficult to explain why. The previous winter, I spent many, many hours reviewing books, articles, and interviews in an attempt to calculate the death toll of the Khmer Rouge regime. Focusing on numbers, however, has the paradoxical effect of making the real nature of the tragedy more abstract. Visiting the killing fields is stark reminder that there is a human dimension that the numbers can never fully reveal.

A friend had suggested that Sang would be relatively easy to find: just ask any of the locals around Tonle Bati.

The first person we ask, however, gives us incorrect directions. We wind up a few miles down the road, at a large temple. My wife asks one of the laymen about the killing field.

Right here, he says. He points to a pavilion-like stupa fifty yards away. The bones are over there.

Yet I know from descriptions that we are not at Sang Prison. Srey explains in greater detail the place we are looking for; during the 1950s, she explains, it was a teacher training college. Oh, the laymen exclaim, and together they point back north. Yes, that's a different place, a few kilometers up the road.

This speaks volumes about the nature of the Khmer Rouge regime: go in search of a killing field, take a wrong turn, and you will merely wind up at a different killing field.

This speaks volumes about the nature of the Khmer Rouge regime: go in search of a killing field, take a wrong turn, and you will merely wind up at a different killing field.

Srey and I are outside, and Anna and Sean are still both sitting in the van, reading. I am wondering what to say when they ask me why we are here, and what this place is.

Srey simply takes the direct approach. She throws open the door of the van. "Do you want to see real skeletons?" she asks.

"OK!" they reply cheerfully, and bounce out of the van.

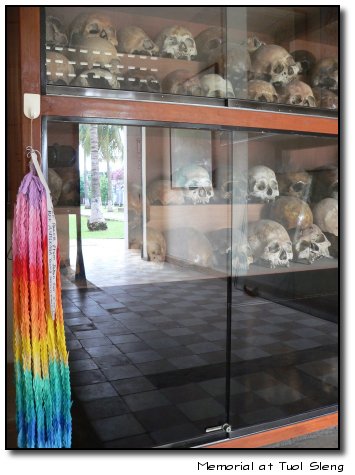

The laymen guide us around the grounds. The stupa was erected recently. Inside, behind glass and iron doors, a pile of skulls and bones is adorned with brightly-colored ribbons. An inscription above the doors, in Khmer and English, reads:

"THIS STUPA WAS RECONSTRUCTED BY MRS. SATH VIBOL TO HONOR MY LOVELY FATHER AND OTHER PEOPLE, WHO WAS TORTURED AND KILLED BY THE GENOCIDE REGIME LASTING 3 YEARS 8 MONTHS AND 20 DAYS (1975 - 1979). YOUR MEMORY WILL STAY IN OUR HEADS FOREVER."

Inside the main temple building, one of the laymen gestures at the walls. On both sides of the building, about every ten yards, a few inches above the floor, there is a small hole bored into the concrete. He lifts his foot toward the hole and clasps his ankle.

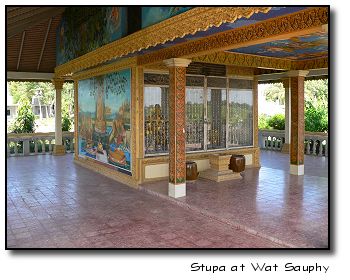

Suddenly I know exactly where I am. People were chained here. This place - Wat Sauphy - is also known as Kokoh Pagoda. I recall a passage from Ea Meng-Try's The Chain of Terror:

"The sanctuary, monks' quarters and school at the wat were used to hold prisoners. The monks' residence west of the sanctuary was turned into an interrogation room. In early 1980, holes were found in the sanctuary walls, which the Khmer Rouge had drilled to anchor leg shackles. There were three rows of shackles; each could hold 30 to 40 persons. The monks' residence south of the sanctuary was used to house interrogators. The fields surrounding the temple in all four directions and the pond in front of the sanctuary became killing fields and gravesites. About 60,000 people were executed at this temple."

In the aftermath of Pol Pot, the walls were stained with blood; now, they have been repainted with murals of Buddha's life. As you face the altar with your head bowed, the small holes in the walls haunt your peripheral vision.

Outside, one can still see the subtle depressions where the bodies were unearthed. Banana trees were planted nearby in the hope that the grounds could be reclaimed for the living. The trees grew quickly, the layman said, but the fruit was no good: it had a strange, salty taste.

Leaving Wat Sauphy, we travel back north and turn onto a small, bumpy dirt road. There is no other traffic except for an occasional bicycle or oxcart. After a while, we can see Bati lake, and then, in the distance, a concrete water tower.

We turn toward the water tower and are soon in a clearing. There is a small stupa, and another simple shelter with open walls and a tin roof. A small sign in front of the stupa carries an inscription in Khmer. Across the clearing, a few broken concrete walls are still standing.

Today, this is all that remains of Sang Prison.

Beneath the tin roof of the shelter, there are a series of paintings at the tops of the open walls. They depict scene after scene of horror: prisoners shacked by the ankles, infants stabbed with bayonets, a woman's stomach being slit. Staring out at these scenes from the corner of the shelter, two larger paintings show the Buddha, sitting serenely in the shade of a bo tree.

Farther away, there are a few small thatch buildings. Our driver begins walking toward them; I stroll through the weeds and debris toward the broken concrete walls. Here and there, one can see the foundation of other buildings, the remnants of an old sidewalk, a deep walled pit that might once have been a basement.

Then the ghosts begin to cry.

Then the ghosts begin to cry.

Our driver hears it first: it is the unmistakeable sound of a child crying, but there is no one there.

From my vantage point, I can see the phantoms. They have four legs, short fur, and horns: goats.

I'm not afraid of spirits. I am, however, a little worried about having an angry goat ramming its horns into my ass.

The goats glance at me, uninterested, and continue walking.

A man comes out from the thatch house. He brings the keys to the stupa and opens its door, revealing a pile of human bones stacked like cordwood.

He tells Srey that there is a rumor that the government wants to build a new prison on the site. "A new tay-buy," says Srey. Tay-buy ("T-3") was Cambodia's most notorious prison during the 1980s, when enemies of the new regime found themselves locked away within its grim walls. Nonetheless, T-3 was at least a prison in the conventional sense, and not simply an extermination facility, like Sang, or Tuol Sleng.

The man tells us that the local farmers are unhappy about the plan. Whether or not it will come to pass remains to be seen. For now, the goats hold sway.

The man tells us that the local farmers are unhappy about the plan. Whether or not it will come to pass remains to be seen. For now, the goats hold sway.

Part 8: Changed City

Back in Phnom Penh in the late afternoon, I walk to the Asia Palace Hotel. Once upon a time, it was Hotel Saw - the White Hotel. In 1991, one of the first pictures I took in Cambodia was a shot of the central market from my room in the White Hotel.

Back in Phnom Penh in the late afternoon, I walk to the Asia Palace Hotel. Once upon a time, it was Hotel Saw - the White Hotel. In 1991, one of the first pictures I took in Cambodia was a shot of the central market from my room in the White Hotel.

The hotel is a good indicator of the change in Phnom Penh over the last 14 years. In 1991, it was badly rundown. The electricity rarely worked (as was the case throughout Phnom Penh), and often there was no water. There were no elevators, or at least no functional elevators.

Now, the hotel gleams. On the ground floor, a Lucky Burger restaurant is crowded with patrons snacking on burgers, fries, and chicken nuggets. As I approach the lobby, a pair of doormen swing open the plate glass doors, and I make my way across the ornate lobby to the front desk. I'm suddenly very conscious my sweat-stained t-shirt and the mud on my shoes. The staff kindly allows me to go to the roof to take several photos.

From the roof, one gets a more realistic assessment of what has and has not changed. New high-rises stand out above the city in every direction, but the overall vista is very similar to what it was years ago. On the balance, Phnom Penh is still poor and dirty... less so than before, certainly, but even a best-case scenario of benevolent, intelligent development will require years to make broad improvements that benefit all of the population.

On the way home, it begins to rain. The water drips down my face, tasting of salt and sweat. I walk past the Holiday Villa hotel; once upon a time, it was the Monorom, a favorite haunt of journalists covering the 1970-75 civil war. A few blocks away is the Royale, another journalists' favorite. Its air of decaying colonial elegance is long gone. It is now the Raffles Hotel Le Royale, and it radiates a haughty corporate air: "International business executives, Welcome: others, please look elsewhere."

On the way home, it begins to rain. The water drips down my face, tasting of salt and sweat. I walk past the Holiday Villa hotel; once upon a time, it was the Monorom, a favorite haunt of journalists covering the 1970-75 civil war. A few blocks away is the Royale, another journalists' favorite. Its air of decaying colonial elegance is long gone. It is now the Raffles Hotel Le Royale, and it radiates a haughty corporate air: "International business executives, Welcome: others, please look elsewhere."

Wednesday, Nov. 30, is spent visiting friends and markets. The Olympic Market and the O'Russey Market. In Cambodian markets, it's expected that you'll haggle over the price. I'm no good at haggling to begin with. How much do I want to argue in order to save a dollar? My inability to bargain was the main reason we brought our Thai friend Sue with us when we had purchased our tickets to Cambodia months ago; Sue argued the price down another $20. Alas, Sue is far, far away now, and we've made the mistake of letting the vendor see that the globe we're asking about is for the seven-year-old standing right next to us. Gee, who has the better bargaining position? Thus the afternoon ends with the boy happily clinging to his new globe, and the vendor in a very good mood over the surprising amount of profit yielded by a cheap-ass Chinese-made globe.

Around Phnom Penh, there are many memories for Srey. As we pass one small neighborhood on the road toward Pochentong, she mentions that she had gone to first grade at a school nearby. She laughs as she recalls how one morning she had gotten into her father's wine, with the result that she became drunk and fell asleep in class later that day. Always the troublemaker.

Phnom Penh today is many ways similar to Bangkok, sixteen years ago. Depending on which direction you are facing, it might be prosperous or it might be poor. It might be modern or it might be ancient. It is a city in transition, distinctly Asian in some ways, decidedly Western in others.

I can't think about cities without thinking about Chicago. I'm ready to go home. I miss my cats, I miss pizza, I miss talking to my Mom every Sunday. I miss television that I actually want to watch: Full Metal Alchemist, Mythbusters, The Simpsons, The Daily Show.

It's our next to last day in Cambodia. In the morning, I visit Tuol Sleng. On the way, we pass a vendor pushing a bicycle laden with all sorts of plastic pans and baskets. It reminds me of the famous method of transit on the Ho Chi Minh trail: bicycles were loaded with supplies and pushed, not ridden, through hundreds of miles of jungle.

It's our next to last day in Cambodia. In the morning, I visit Tuol Sleng. On the way, we pass a vendor pushing a bicycle laden with all sorts of plastic pans and baskets. It reminds me of the famous method of transit on the Ho Chi Minh trail: bicycles were loaded with supplies and pushed, not ridden, through hundreds of miles of jungle.

Thinking of the Ho Chi Minh trail naturally leads to thinking about history, and about mistakes. A cynic might regard history as the study of mistakes. In 1989, scholar Frances Fukuyama wrote an essay called "The End of History?" in which he argued that, with the collapse of communism, history was essentially over, and the liberalism had won.